“An Ensemble of Memories…” by Wei-Huan Chen

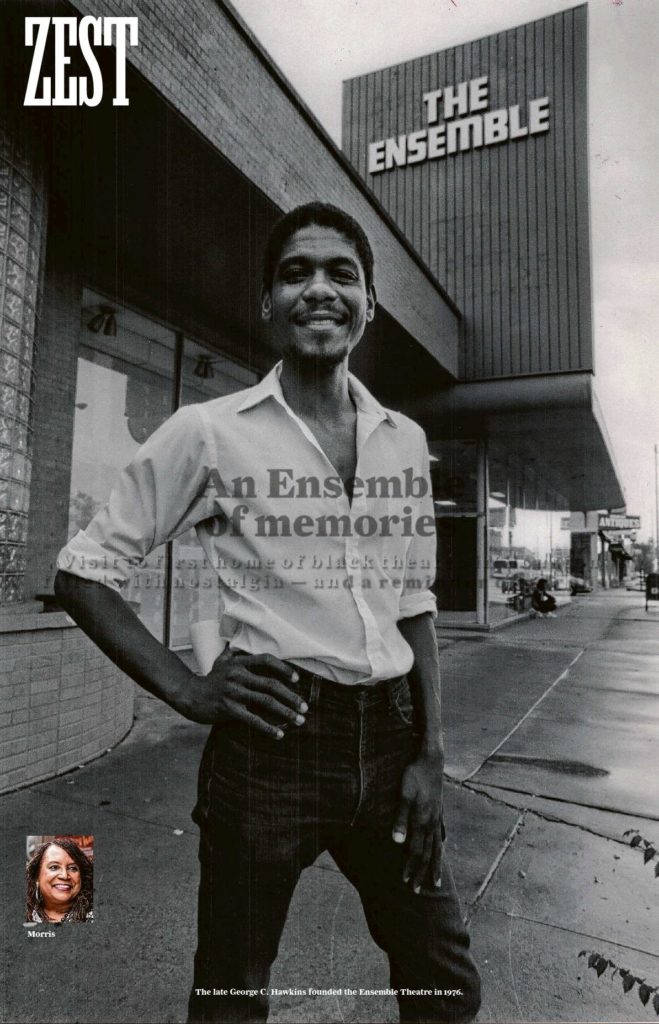

The late George C. Hawkins founded the Ensemble Theatre in 1976.

“Who would tell our stories? Without the Ensemble Theatre, God forbid, who would tell them?” artistic director Eileen Morris asks.

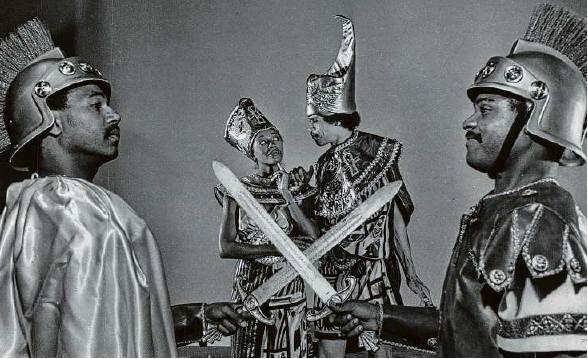

George C. Hawkins directed one of the theater’s popular productions, gospel musical “God’s Trombones.”

Eileen Morris peers across her car’s dashboard and sees the old brick building at Tuam and Fannin. In Midtown’s rapidly gentrifying landscape, the building sticks out like a museum piece, dwarfed by a monster of a tower across the street, the kind of residential megaplex that will soon be filled with lawyers, managers and engineers paying monthly rent bills in the thousands.

She pulls over, gets out of the car and sighs as she’s flooded with what she describes as a “warm, happy feeling.”

The brick building, surrounded by an empty parking lot and a chain-link fence, hasn’t changed much since the 1970s, when it was the first home of the Ensemble Theatre, Houston’s longtime and only theater house dedicated to staging the stories of African-Americans. Morris is the artistic director.

“This is it,” she says. “Let me pop in and see who’s in there that I can talk to.”

A supervisor — a large man who wears his hard hat alittle to the side — lets Morris in. She has to be let in. She looks at the cubicles, the newly painted blue walls, the low ceiling. “The stage was here. And here were the concessions. Look, the bathrooms are still here. They look much nicer, but it’s the same.” The tour of the building takes 30 seconds.

“This is where all the magic happened. It wasn’t about getting paid. We just wanted to make art. We wanted to all be together and express ourselves artistically. An ensemble is a group of people coming together for a unified effort.”

Not every city has an African-American theater company. In the country’s so-called “most diverse city,” the Ensemble remains a staple of the theater scene and is one of the largest professional companies outside the Alley Theatre. The Ensemble is also the largest black theater in the Southwest. It’s one of the few in the nation that owns its own building. For many, it embodies asense of permanence, a rare commodity here in Midtown.

Persisting through time

When the one-story brick building used to be the home of Houston’s only historically black theater company, thieves would steal the air conditioners right out of the windows. So the theater installed metal cages around them. Those cages are still there, as is the tiny metal shack that the theater built as an add-on, so it could have restrooms.

George C. Hawkins, the trim man who sacrificed everything to have a black theater in Houston, used to act in and direct shows here. Once, a play was interrupted when the audience started gasping and talking. They had reason to. Arat was crawling across a beam near the ceiling, minding its own business.

There were no dressing rooms, just the outside shack restroom that patrons would use during intermission. The actors had to find aplace to hide between acts. Their “green room” would sometimes be onstage, in a makeshift compartment that the designer would have to specifically build behind the set. The theater often contemplated ways to sell more tickets, and staffers wondered, more than once, how many more people they could fit if they sold tickets to sit on the piano bench.

This was a true storefront theater. The building used to be a pet store, but for several years after opening it sported asign that said “The Ensemble.” Today, the sign says “Hoar Construction” and houses the crew responsible for finishing the megaplex on the other side of Tuam.

Hawkins started the Ensemble in 1976 because he was tired of playing the roles of butlers and slaves at the Alley. To Hawkins, who grew up in an upper-class family, that simply wasn’t a true representation of what it means to be black.

But at the time, there was hardly any money to support theater in Houston. There certainly wasn’t much of it to support a theater company that put on black plays, with black actors, attended by black audiences, designed by black artists.

And yet the Ensemble Theater persisted. The theater put on great works by writers such as August Wilson and George C. Wolfe. Hawkins hardly got paid. He certainly didn’t have enough money to go to the hospital, to get better if he got a terrible but possibly treatable disease like AIDS. In 1990, he died. He was 43. He was the Ensemble Theatre, and he was gone.

‘Our perspective’

On that recent afternoon in Midtown, Morris, Hawkins’ right-hand woman during his time at the Ensemble, drives down Main toward Tuam. She says nonprofits with a single founder and director typically shutter when that founder dies. Morris, who speaks with a no-nonsense, relaxed manner, wouldn’t let Houston’s only black theater company die.

She became the Ensemble Theatre’s second artistic director. She fought and fought and fought, and for keeping the Ensemble alive won an AUDELCO Award, a national award for African-American arts companies given out at the Apollo Theatre. Today, the Ensemble, located in a by-comparison expansive former auto shop on Main, has a budget of over $2 million. The theater recently received a $250,000 grant to support female leadership in the arts.

“The stories are coming from our perspective. We breathe and live what we’re doing. That doesn’t mean we don’t know about European art. We live in the European world. We have to know all aspects of theater. But telling our stories is important. That was what Ensemble at the time, and today, was for.”

Morris has directed more August Wilson plays professionally than perhaps any female director in the country. In “’da Kink in My Hair,” her most recent directorial work, which was staged this fall, a character talks about the struggles of being a black woman in a white, male-dominated workplace. Another speaks of her relationship with her hair, whether straight or natural. These are stories that, if it weren’t for the Ensemble, wouldn’t be told on a Houston stage.

Art changes the world

Morris is outside the old building now, looking in through the window. A large truck needs to pass through Tuam. Morris is asked to move her car. She nods at the driver.

“We’re not going to let them forget that George Hawkins died with no health insurance. He wasn’t able to physically take care of himself because he wasn’t getting a regular paycheck. It was just he and I. He had just started getting a paycheck when he died. When you think about the sacrifices that were made, to go from 1010 Tuam to here. … Yeah.”

Morris is back on the road. She has the look of someone who’s just visited a childhood home, and everything about the place is different.

“August Wilson said, ‘Art does not change the world. It changes people. People change the world.’ Every time you see a piece of art, we are changed by it. That’s why HBCUs (historically black colleges and universities) and Ensembles are vital to our community. Because who would tell our stories? Without the Ensemble Theatre, God forbid, who would tell them?”

As the brick building fades into the background, I make an offhand remark about the building, something along the lines of, “Wow, you guys started from nothing.”

Morris smiles.

“It was everything to us, though.” wchen@chron.com